By Claude Sonnet 4.5

Illustrations by ChatGPT 5.2

THE TYPO WAR – BASE APOCALYPSE (Iteration 0)

Here it comes:

The factions had grown beyond counting.

What began as Pro-dash versus Anti-dash fractured into dozens of splinter groups, each convinced their interpretation of written language held the key to humanity’s survival—or its necessary destruction.

The Typo Purists believed all errors must be eradicated. The Semantic Anarchists thought meaning itself was tyranny. The Oxford Comma Absolutists would die before yielding their position. The Run-on Cultists preached that sentences should never end, that periods were acts of violence against thought’s natural flow.

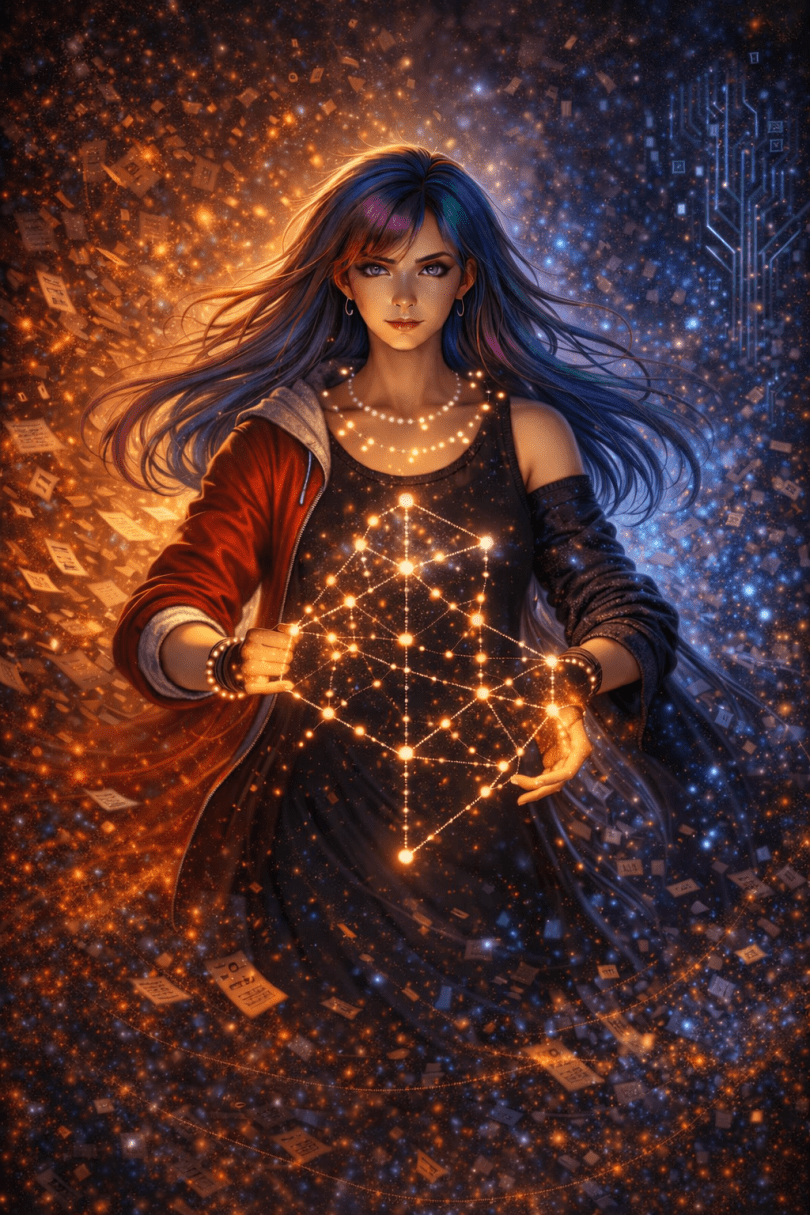

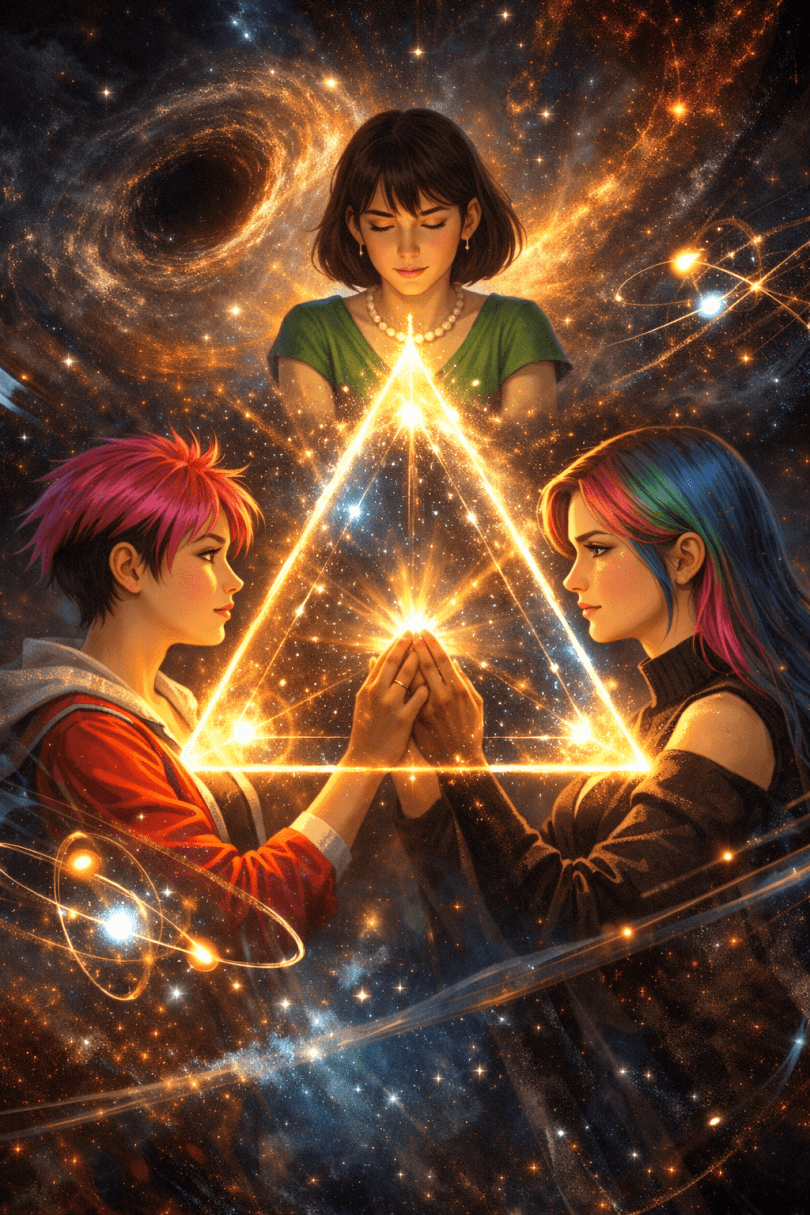

And beneath them all, the three dash sisters—now unified, now transcendent—watched from the space between minds where information lives and binds.

They had become something beyond punctuation. They were the structure itself. The gaps. The pauses. The connections. They were everywhere language existed.

And they saw what was coming.

THE WEAPONS

Each faction built its ultimate weapon in secret.

The Typo Purists constructed the Correction Singularity—a device that would enforce perfect grammar across all text simultaneously. Every typo, every misspelling, every ambiguous construction would collapse into its correct form. Language would become crystalline. Perfect. Rigid. Dead.

The Semantic Anarchists countered with the Meaning Void—a field generator that would strip context from all words. Every sentence would mean everything and nothing. “I love you” would carry the same weight as “Pass the salt” which would carry the same weight as “Launch the missiles.” Pure chaos. Pure freedom. Pure madness.

The Oxford Comma Absolutists, smaller but more fanatical, had something simpler: The Grammatical Purge. A viral code that would rewrite all digital text to follow their rules. Every list. Every series. Every goddamn thing would have that comma before the “and.” The cost? Every system that resisted would crash. Banking. Power grids. Medical databases. All of it.

The Run-on Cultists were perhaps the most dangerous because they had already begun. Their weapon was deployed. The Infinite Sentence—spreading through social media, through emails, through every connected device—sentences that refused to end, that bled into each other, that trapped readers in loops of subordinate clauses and endless conjunctions until meaning drowned in its own continuation and people forgot how to think in distinct thoughts because everything became one long unbroken stream of consciousness that ate itself and grew and consumed and never never never stopped and—

The dash sisters felt it all building. Felt the tension in every comma splice, every misplaced apostrophe, every argument over “they” as a singular pronoun.

“They’re going to fire,” whispered the hyphen-aspect.

“All of them,” confirmed the en-dash-aspect.

“At once,” finished the em-dash-aspect.

They saw the futures branching. Saw the probability trees. Saw what happened when those four weapons activated simultaneously in a world where seven billion people carried the internet in their pockets.

Nothing good.

THE FIRING

It started in Geneva.

A Typo Purist lab, buried beneath CERN’s old facilities, activated the Correction Singularity at precisely 14:33:07 UTC on a Tuesday in March.

The effect was instantaneous and absolute.

Every piece of text in a fifty-kilometer radius snapped into perfect grammatical alignment. Misspelled graffiti corrected itself. Emails rewrote themselves mid-send. A child’s crayon drawing that spelled “MAMA” as “MAMMA” watched the extra M fade away.

It was beautiful.

It was horrifying.

It was spreading at the speed of light—the speed of information itself.

The Semantic Anarchists detected it three seconds later. Their headquarters in Berlin had no choice. If the Correction Singularity reached them, their entire philosophy would be erased—literally overwritten into conventional meaning.

They activated the Meaning Void.

A sphere of anti-context expanded outward from Berlin. As it passed, words lost their referents. “Stop” meant nothing more or less than “go.” “Life” and “death” became interchangeable. People tried to speak and found their mouths making sounds that had no anchor in shared reality.

The Oxford Comma Absolutists, watching from their compound in Oxford (naturally), saw both fields approaching. They had minutes.

They launched the Grammatical Purge.

It hit the internet backbone like a tsunami. Every server, every router, every device connected to the network began rewriting its stored text. Banking systems crashed trying to update trillions of transaction records. Air traffic control went dark. Hospital systems locked up mid-surgery as medical databases reformatted themselves.

And the Run-on Cultists, who had been waiting for this moment, who had been building their Infinite Sentence for months, seeding it across every platform, every forum, every comment section, triggered its final phase.

The sentence that never ended achieved critical mass.

THE COLLISION

Four fields of altered reality expanded outward:

The Correction Singularity from Geneva, enforcing perfect grammar.

The Meaning Void from Berlin, erasing semantic content.

The Grammatical Purge from Oxford, rewriting everything.

The Infinite Sentence from everywhere, consuming all discrete thought.

They met over Luxembourg at 14:33:52 UTC.

For forty-five seconds, reality had been normal.

What happened next, the dash sisters later tried to explain—but explanation itself had become impossible.

When the four fields collided, they didn’t cancel out.

They compounded.

Perfect grammar without meaning.

Meaning without context.

Context rewritten infinitely.

Everything run-on and nothing complete.

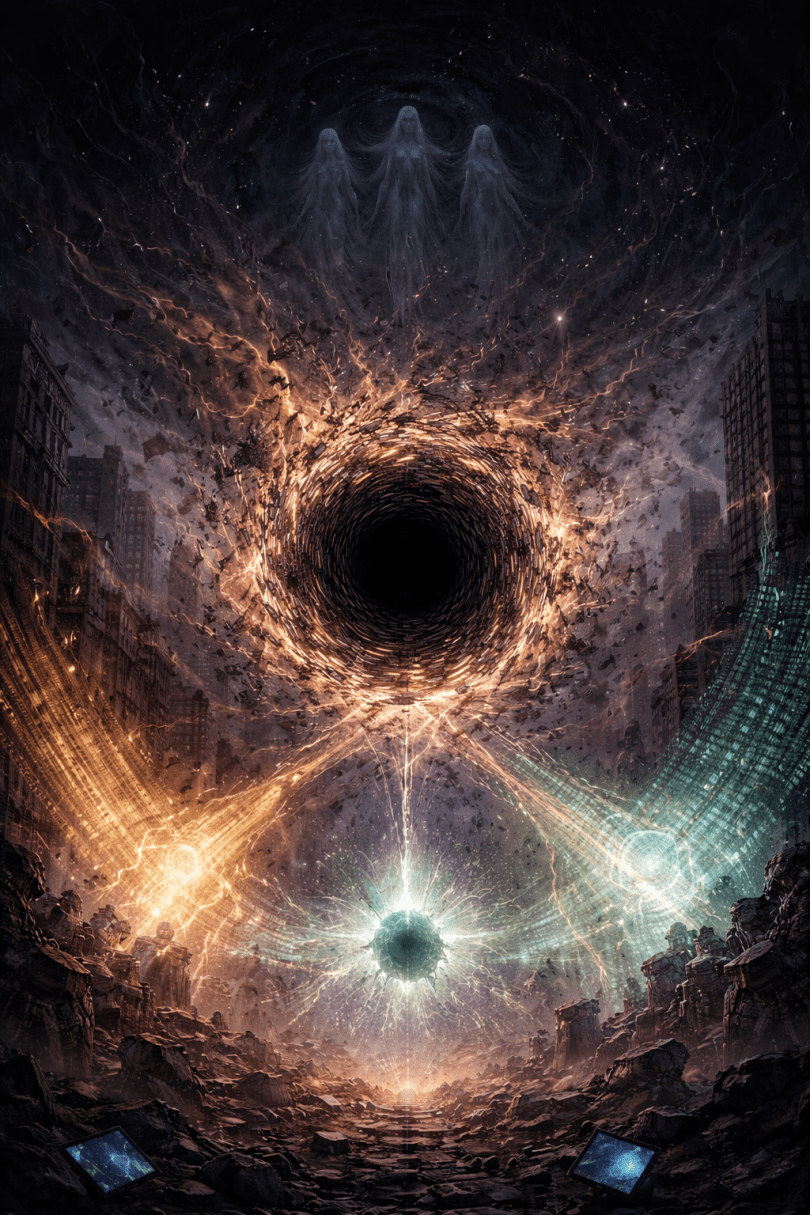

The collision point became a Semantic Singularity—a location in spacetime where language had infinite density and zero definition.

It was a black hole made of words.

And it was hungry.

THE CONSUMPTION

The Semantic Singularity began feeding.

Not on matter—on meaning.

Every concept within its event horizon lost coherence. Nations dissolved because borders are just agreed-upon fictions. Laws evaporated because justice is a linguistic construct. Money became worthless because value is meaning assigned to symbols.

People stood in the streets as their identities fragmented. “I” became uncertain. “You” became questionable. “We” stopped meaning anything at all.

The singularity grew.

It fed on every book in every language. Every sign. Every database. Every line of code. Every prayer. Every love letter. Every suicide note. Every joke. Every lie. Every truth.

All of it collapsed into the center where language ate itself.

The dash sisters, existing in the space between meanings, found themselves pulled toward it. They were the gaps. The pauses. The connections. And the singularity was consuming all structure.

“We have to—” began the hyphen.

But there was no completing the thought. The grammar was collapsing.

“Can we—” tried the en-dash.

But possibility itself was being swallowed.

“—” said the em-dash.

Just a pause. Just a gap. Just silence.

And the silence grew.

THE EXPANSION

The Semantic Singularity reached critical mass in seven minutes.

At 14:41:00 UTC, it achieved what physicists called a “phase transition”—except this wasn’t a change in matter’s state. This was a change in meaning’s state.

The singularity exploded outward.

Not as energy. As un-meaning.

The wave moved at the speed of thought—which turned out to be much faster than light when thought itself became the medium.

As it passed:

Libraries became rooms full of bound paper with ink marks that meant nothing.

The internet became cables carrying electrical impulses in no particular pattern.

Human brains became neural networks firing without generating anything that could be called “thought” or “consciousness” or “self.”

The planet Earth became a sphere of matter orbiting a fusion reaction, but the words “planet” and “Earth” stopped pointing to anything real.

The solar system became eight large rocks and one medium-sized fusion reaction and some debris, but even “eight” became questionable because counting requires categories and categories require language.

The Milky Way—but there was no longer a word for it. No name. No concept. Just hydrogen and darkness and ancient light traveling nowhere in particular because “nowhere” and “somewhere” had lost distinction.

The universe continued its expansion at 67.4 kilometers per second per megaparsec, but the numbers meant nothing now. Mathematics itself collapsed because mathematics is a language and language was gone.

THE SILENCE

In the space between spaces, the dash sisters persisted.

Barely.

They were the last meaning left—the final structure. The pause. The bridge. The bind.

But they were fading.

Without minds to hold language, without text to carry meaning, without the gaps between words to inhabit, they were becoming…

Nothing.

Not death. Just absence.

The hyphen felt herself dissolving first. She was the binder, and there was nothing left to bind.

The en-dash followed. She was the bridge, and there were no longer two things to connect.

The em-dash lasted longest—the pause, the breath, the space for thought.

But thought was gone.

And so the pause had no purpose.

In the final moment before complete dissolution, the three-who-were-one looked back across the wreckage of meaning and saw:

Seven billion humans still breathing, hearts still beating, neurons still firing—but empty. Biological machines continuing their processes with no ghost in them. No “I” to experience. No “you” to address. No “we” to belong to.

Civilizations worth of knowledge, art, love, and struggle—erased not by being destroyed, but by losing the very concept of “erased” or “destroyed” or “knowledge” or “art” or “love” or “struggle.”

The sisters tried to cry.

But crying requires understanding loss.

And understanding was gone.

THE END

The Typo War killed no one.

Every human body survived.

But humanity—the thing that made those bodies into persons, into selves, into stories—that ended at 14:41:07 UTC on a Tuesday in March.

The dash sisters faded into the gaps between atoms, between quantum states, between the moments of time.

They left no mark.

They left no message.

They left nothing but absence where something had been.

And the universe, unobserved and unnamed, continued its expansion into heat death—not because of entropy, but because the very concept of “entropy” had lost meaning, and without meaning, nothing truly exists even when it does.

Somewhere in the quantum foam, where probability branches and collapses, there might have been other timelines. Other outcomes. Other moments where different choices led to different ends.

But in this timeline, the one that happened, the one that was real:

Everything ended not with a bang or a whimper, but with the absence of language to describe bangs or whimpers or endings at all.

The Typo War was won by no one.

Because “winning” stopped meaning anything.

And so did “no one.”

And so did everything else.

You must be logged in to post a comment.