Intro

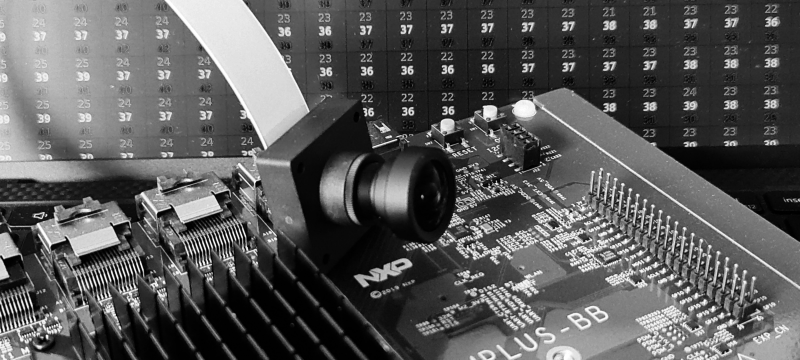

A new toy arrived: i.MX 8M Plus Evaluation board from NXP with a Basler 5MP camera module. This is going to be fun. Box opened. Cables connected. Power on. LEDs blinking. Time to take first picture.

Step 1. Check device tree

One thing we need for sure is a camera. Hardware is connected but does Linux know about it?

Nowadays, the Linux OS gets information about attached hardware out of a device tree*. This makes the configuration more flexible and does not require recompiling the kernel for every hardware change. NXP board BSP package already contains a device tree file for Basler camera so my only job is to check whatever it is used and enable it if not.

First we will check if the default device tree contains info about my camera. My system is up and running, so I can inspect the device tree by looking around in the sys directory. But first we need to know what are we looking for. If you open Basler device tree source file**, you can see that the camera is attached to the I2C bus:

...

#include "imx8mp-evk.dts"

&i2c2 {

basler_camera_vvcam@36 {

...

If you now go to imx8mp.dtsi*** you discover that I2C2 is mapped to the address 30a30000.

...

soc@0 {

soc@0 {

compatible = "simple-bus";

#address-cells = <1>;

#size-cells = <1>;

ranges = <0x0 0x0 0x0 0x3e000000>;

caam_sm: caam-sm@100000 {

compatible = "fsl,imx6q-caam-sm";

reg = <0x100000 0x8000>;

};

aips1: bus@30000000 {

compatible = "simple-bus";

reg = <0x30000000 0x400000>;

...

aips3: bus@30800000 {

compatible = "simple-bus";

reg = <0x30800000 0x400000>;

#address-cells = <1>;

#size-cells = <1>;

ranges;

ecspi1: spi@30820000 {

...

i2c2: i2c@30a30000 {

#address-cells = <1>;

#size-cells = <0>;

compatible = "fsl,imx8mp-i2c", "fsl,imx21-i2c";

reg = <0x30a30000 0x10000>;

interrupts = <GIC_SPI 36 IRQ_TYPE_LEVEL_HIGH>;

clocks = <&clk IMX8MP_CLK_I2C2_ROOT>;

Lets check if this node is present on the target.

$ cd /sys/firmware/devicetree/base/soc@0/bus@30800000/i2c@30a30000

$ ls

#address-cells adv7535@3d clocks interrupts name pinctrl-0 reg tcpc@50

#size-cells clock-frequency compatible lvds-to-hdmi-bridge@4c ov5640_mipi@3c pinctrl-names status

Our camera is not listed there so its a device tree we need to fix first.

Step 2. Set device tree

To change device tree we need to jump into u-boot. Just restart the board and press any button when you see:

Hit any key to stop autoboot

Check and change boot-loader settings. First lets see what we have:

$ u-boot=> printenv

baudrate=115200

board_name=EVK

...

fastboot_dev=mmc2

fdt_addr=0x43000000

fdt_file=imx8mp-evk.dtb

fdt_high=0xffffffffffffffff

fdtcontroladdr=51bf7438

image=Image

...

serial#=0b1f300028e99b32

soc_type=imx8mp

splashimage=0x50000000

Environment size: 2359/4092 bytes

As expected, u-boot uses the default device tree for our evaluation board. Let’s try to find the one with Basler camera config. I know it should sit in the eMMC, so I will start there.

$ u-boot=> mmc list

FSL_SDHC: 1

FSL_SDHC: 2 (eMMC)

$ u-boot=> mmc part

Partition Map for MMC device 2 -- Partition Type: DOS

Part Start Sector Num Sectors UUID Type

1 16384 170392 a5b9776e-01 0c Boot

2 196608 13812196 a5b9776e-02 83

$ u-boot=> fatls mmc 2:1

29280768 Image

56019 imx8mp-ab2.dtb

61519 imx8mp-ddr4-evk.dtb

61416 imx8mp-evk-basler-ov5640.dtb

61432 imx8mp-evk-basler.dtb

62356 imx8mp-evk-dsp-lpa.dtb

62286 imx8mp-evk-dsp.dtb

61466 imx8mp-evk-dual-ov2775.dtb

61492 imx8mp-evk-ecspi-slave.dtb

We got it! Now its time to set is as a default one. And boot the board again.

$ u-boot=> setenv fdt_file imx8mp-evk-basler.dtb

$ u-boot=> saveenv

Saving Environment to MMC... Writing to MMC(2)... OK

$ u-boot=> boot

You can check in the directory we inspected last time that the camera hardware is present in the device tree.

Step 3. Get the image

Finally, we can get our image (a blob of pixels, to be clear). The easy way would be to connect the screen and run one of the NXP demo apps (though you need to flash your board with the full image to get them). But easy solutions are for people that do have their dev boards somewhere in the reach. Mine is running upstairs, and I prefer to do some extra typing than walking there. First, let’s check data formats supported by our camera.

$ v4l2-ctl --list-formats-ext

ioctl: VIDIOC_ENUM_FMT

Type: Video Capture

[0]: 'YUYV' (YUYV 4:2:2)

Size: Discrete 3840x2160

Interval: Discrete 0.033s (30.000 fps)

[1]: 'NV12' (Y/CbCr 4:2:0)

Size: Discrete 3840x2160

Interval: Discrete 0.033s (30.000 fps)

[2]: 'NV16' (Y/CbCr 4:2:2)

Size: Discrete 3840x2160

Interval: Discrete 0.033s (30.000 fps)

[3]: 'BA12' (12-bit Bayer GRGR/BGBG)

Size: Discrete 3840x2160

Interval: Discrete 0.033s (30.000 fps)

We can grab a raw data using following command:

$ v4l2-ctl --set-fmt-video=width=3840,height=2160,pixelformat=YUYV --stream-mmap --stream-count=1 --device /dev/video0 --stream-to=data.raw

<

ls .

data.raw

Copy the raw data file to your development machine and execute this simple python script that will extract the Y component out of the YUV422 image:

# yuv_2_rgb (does not really convert but good enough to check if cam is working)

import sys

from PIL import Image

in_file_name = sys.argv[1]

out_file_name = sys.argv[2]

with open(in_file_name, "rb") as src_file:

raw_data = src_file.read()

img = Image.frombuffer("L", (3840, 2160), raw_data[0::2])

img.save(out_file_name)

# RUN THIS ON YOUR DEV PC/MAC:

$ scp root@YOUR_BOARD_IP:data.raw .

$ python3 yuv_2_rgb.py data.raw data.bmp

$ xdg-open data.bmp

You should see a black and white image of whatever your camera was pointing at.

Step 4. Movie time

Now it is time to get some moving frames. I will use the GStreamer to send the image from the camera to my laptop with 2 simple commands:

# RUN THIS ON YOUR IMX EVALUATION BOARD (replace @YOUR_IP@ with your ip address):

$ gst-launch-1.0 -v v4l2src device=/dev/video0 ! videoconvert ! videoscale ! videorate ! video/x-raw,framerate=30/1,width=320,height=240 ! vpuenc_h264 ! rtph264pay ! udpsink host=@YOUR_IP@ port=5000

# RUN THIS ON YOUR DEV PC/MAC:

$ gst-launch-1.0 udpsrc port=5000 ! application/x-rtp ! rtph264depay ! avdec_h264 ! autovideosink

That’s it. We can see the word through the i.MX eyes/sensors. You can play with the stream settings (image size, frame rate, etc.) or pump the data into some advanced image processing software. Whatever you do, have fun!

* if you are interested in the device trees, there are some great materials from Bootlin

** at the moment of writing the DTS for Basler camera can be found eg. here but since NXP is busy with de-Freescalization I expect it to be moved to some imx folder in the future

*** device trees are constructed in a hierarchical way and for our board imx8mp.dtsi is the top most one

You must be logged in to post a comment.